The San Jacinto Mountains are a hiker’s paradise, with more than 200 miles of trail to explore. We owe a debt to many for pioneering and developing such a superb resource, among them Cahuilla Indians, ranchers, 19th-century campers and innkeepers, individual explorers and entrepreneurs, the U.S. Forest Service, the California State Park Service and the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).

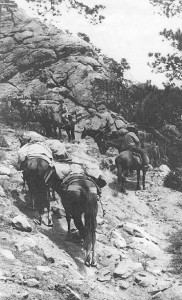

The primary gateway to the high country above Idyllwild is the Devil’s Slide Trail from Humber Park to Saddle Junction. As you hike it, try to imagine the earliest traffic up this mountainside — herds of cattle. The idea of cows scrambling straight up the steep headwall of Strawberry Valley may seem preposterous, but between about 1870 and 1900 the migration to summer pastures from the dry flatlands below was an annual ritual.

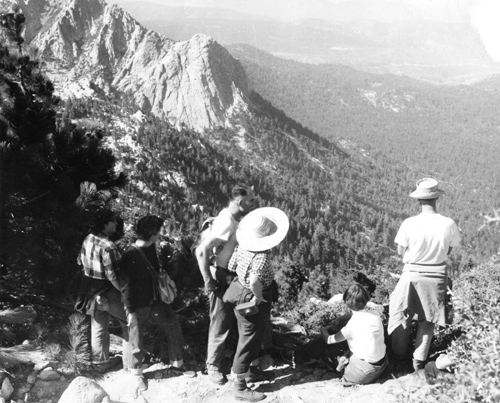

Today’s Devil’s Slide Trail is a vast improvement over several prior routes, such as the one you can still spot zigzagging down the mountainside just below Saddle Junction. At the 8,000-foot-high junction, four trails fan out. Proceed straight ahead toward Long Valley, and you’ll be following in the wake of the earliest guides and campers, who in the 1880s pioneered this roundabout approach to San Jacinto Peak via Hidden Lake and Round Valley, commonly on horseback.

Take a left turn at Saddle Junction, and you’re on what was originally called the “Government Trail,” the first one built by federal rangers after creation of the San Jacinto Forest Reserve in 1897. It opened a shorter route to San Jacinto Peak via Wellman’s Cienega, but many riders wishing to avoid Devil’s Slide and the cattle drive opted for the longer, less strenuous path up South Ridge, passing by Tahquitz Peak on their way to Round Valley.

After Idyllwild was officially born in 1901, excursions into the high valleys became so popular, entrepreneurs occasionally set up tent camps at Tahquitz or Round Valley meadows to house and feed overnight guests. But none of these enterprises succeeded well enough to last more than a season or two.

Veering slightly to the right at Saddle Junction steers you toward Laws Camp and the Caramba overlook via the upper section of the Gordon Trail. This path was named for Palm Springs resident Moses Gordon, who built it in 1916-17 as a way to get from home to his Idyllwild cabin. The extremely steep section up Tahquitz Canyon below Caramba was a nightmare to maintain, soon became impassable, and was abandoned after a few years.

A hard right turn at Saddle Junction puts you on the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT), heading toward the Desert Divide, which stretches for some 23 miles from Tahquitz Valley in the high country south to Highway 74 beyond Garner Valley. Despite its unimpressive appearance from the highway, the divide offers surprisingly interesting terrain for PCT hikers. One striking access route is the Spitler Peak Trail up from Apple Canyon Road. The PCT section from there north to Tahquitz Valley was scratched out in 1967 by another intrepid explorer, one Sam Fink.

The popular alternative to Devil’s Slide for Idyllwild visitors seeking wilderness solitude is the Deer Springs Trail, a sample of the 26 miles of trail built by the CCC in the 1930s. Its popularity rests mainly on a branch that crests the top of Suicide Rock, offering a spectacular view of Strawberry Valley below. But staying on the main trail beyond that turnoff can take you all the way to San Jacinto Peak.

Some high country visitors avoid the initial climb by riding the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway to Mountain Station, which sits at 8,400 feet overlooking Long Valley. This aerial ride is a dramatic shortcut compared to the earliest trails into our mountains that were created millennia ago by Cahuilla Indians from the Palms Springs area. They came to the high country each summer to supplement their winter food supply, following trails up all the major canyons on the sheer north and east sides of the range.

If you wish to get away from summer crowds, there are several less-used alternatives. My personal favorite is the Fuller Ridge Trail from the end of the Black Mountain Road to Deer Springs, with its trailhead at 7,700 feet, knife-edge terrain, and spectacular view of the north face of the highest peaks. Several summers were required in the early 1960s to create this trail as a segment of the PCT.

Closer to home, the Ernie Maxwell Scenic Trail, overlooking Idyllwild along the lower flank of South Ridge, got its name in 1986, but was built in 1959-60 with laborers provided by the Forest Service, county prison and local community. According to its namesake, Idyllwild icon Ernie Maxwell, it was intended as a bypass route for horsemen to relieve them of tangles with automobile traffic between Humber Park and the downtown stables. Its gentle slope and proximity to the village have gradually turned it into our most popular walking path for family outings.

Over the past century, many of these trails have been rebuilt and improved by the Forest Service, State Park and California Conservation Corps, leaving us a rich array of ways to immerse ourselves in a forest wilderness.