Charles M. Province’s list of published works include no less that 11 titles about General George Patton, (including one focused on the allegation that he was assassinated by the powers that be). His latest work is “Jon Gnagy — America’s Art Teacher.” Gnagy, to those not old enough to remember, hosted a long-running series of art lessons that were a staple of early television. The book comes to the Crier for review, and we present it to our readers because Gnagy spent a long spell on “the Hill,” residing here, teaching and making art from 1960 until his death in 1981. At various times he had a studio (since burned down) near present-day Mile High Cafe, and gave regular public demonstrations at the old Welch’s Carriage Inn.

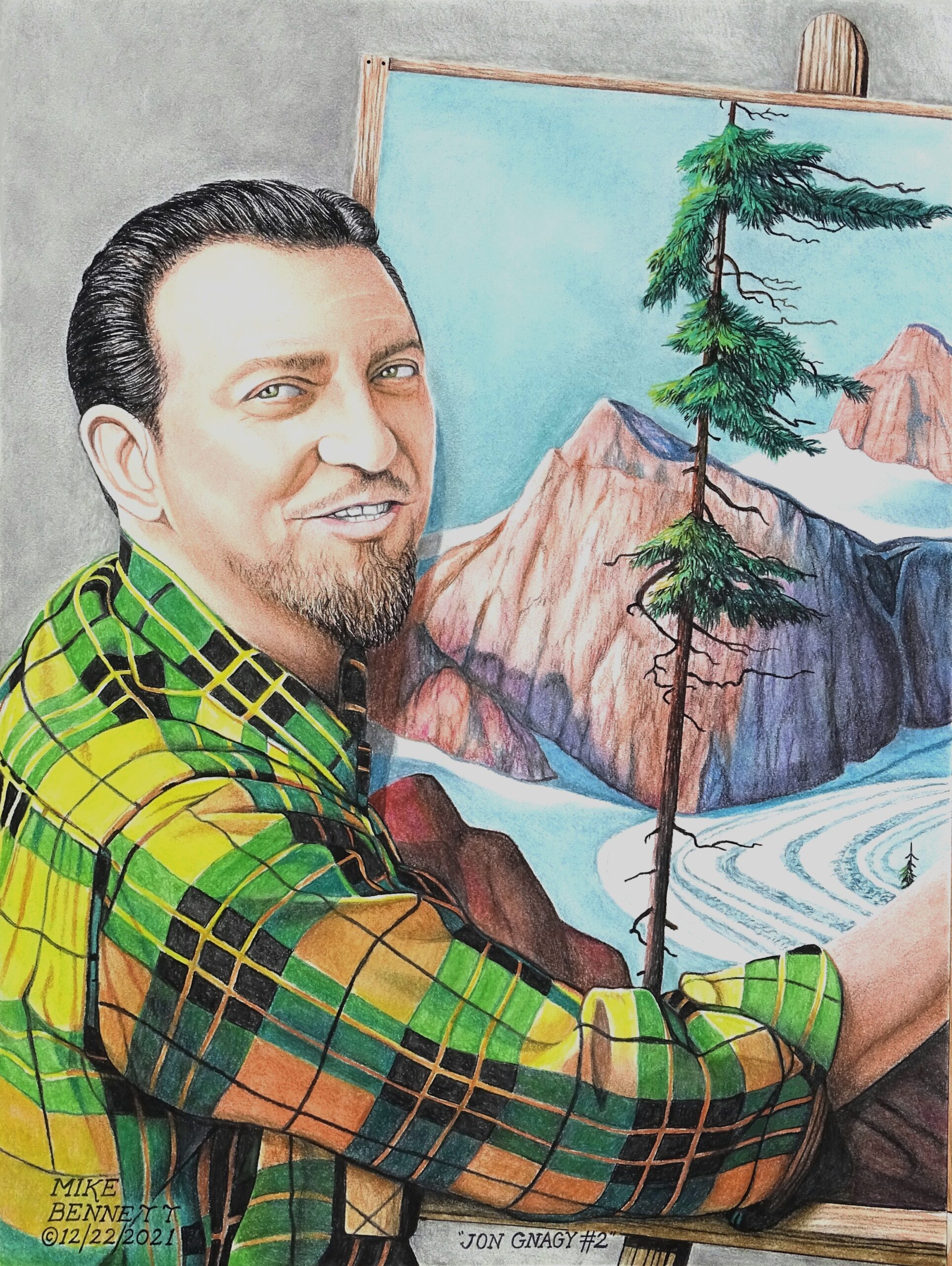

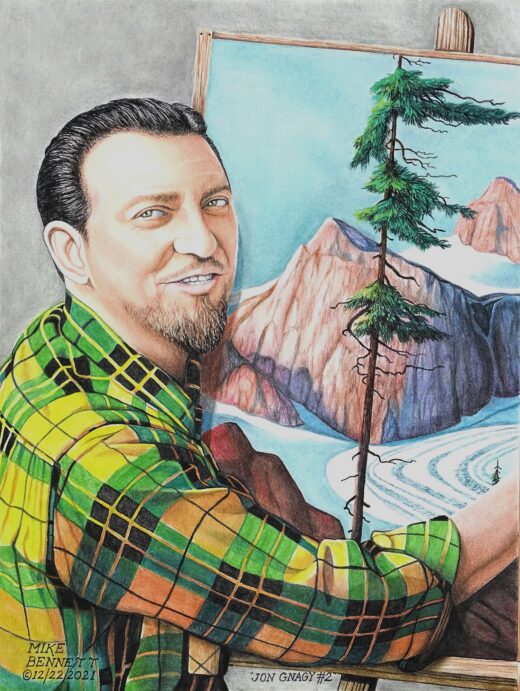

By Mike Bennett

Gnagy’s story is one worthy of an artist: his birth to a Mennonite family in Kansas in 1907, the early recognition of his talent and vocation, the years of hardship during the Great Depression, and his bout with depression and shock therapy. From this he emerged more dedicated than ever and more sure of his mission.

Gnagy’s motto was “You are an artist.” His televised lessons and books taught that the student could draw anything with four basic shapes (cube, cylinder, cone, sphere.) He was a great encourager, leading generations to pick up a pencil (or order a kit) and follow along.

What viewers could never guess was that these relaxed, intimate, 15-minute lessons in which a drawing appeared line by line, each action explained to the student, were intensely rehearsed. Each week he would write a script of 2,000 words, memorize it, and practice delivering it while sketching in front of a mirror. Then he would try his lesson out on a “lay person,” a studio technician, asking them to stop him if anything he said was not clear. Only then was the program broadcast. Most viewers found it impossible to keep up with the master, but the purpose was to get people started, to teach that even their first drawing could be fun, recognizable and, maybe, beautiful.

Gnagy was a true TV pioneer; when NBC began commercial telecasts in 1946 from its studio in the Empire State Building, the first show included celebrity gossip, comic skits, a chef and Gnagy. He always treasured the floor manager’s compliment when he walked off the set after his first segment; “Jon, that was great. Your show was pure television.” Gnagy understood the technical and emotional aspects of the new medium like few others. He also understood the business end; his shows were unpaid work, but he advertised his books and art materials (available at an art supply store near you.) His sketches he donated to be auctioned for charity.

His ambition never flagged, and when TV went color, he experimented tirelessly to perfect a quick color painting process, but never made the transition. Gnagy retired from the TV shows, fished more, and moved to Idyllwild.

Beyond a biography, the book serves as an archive of all things Gnagy. Several chapters consist entirely of reproductions of the artist’s work, spanning beyond his well-known landscapes to illustrations done for his high school magazines and yearbooks, and graphic art for advertising clients. Sixteen pages of plates illustrate “game” fish, both salt and fresh water, illustrations from “Peterson’s Field Guide to Pacific Coast Fishes” and “Field and Stream” magazine, and a thick collection of Gnagy’s own fish stories, some of which gear manufacturers commissioned (and a beer company — he was a marketing genius.) A few delightful teasers are sprinkled among the over 400 pages, including the quote from Andy Warhol, that “Jon Gnagy taught me to draw.”

The book also includes profiles of two students of his who still live in the Inland Empire — Mike Bennett in Beaumont and Henry Balzer in Redlands. Bennett only had a few contacts with his mentor but Balzer studied privately with him in his Idyllwild home studio. Both artists are advocates for their mentor and helped to “sketch” him for this article.

Mike Bennett, then aged 11, met Gnagy at the 1966 grand opening of the San Bernardino May Company, where the artist was doing a demo lesson for children. He still has the drawing he completed that day, and has since done many variations on it. Gnagy’s paintings are like that; iconic compositions that several generations of aspiring artists have “covered” repeatedly.

MB: “He reached into people’s living rooms. I was a kid in the 60s watching reruns; he was flawless. I got hooked. At least 10 of these old programs are now on YouTube. Gnagy was the greatest influence on my artistic talent. God gave me the talent, but Gnagy lit the torch. The rest was just practice and observation.”

Bennett was inspired not just to be a professional artist (those licensing payments add up) but also an educator. He now works for the Yucaipa/ Calimesa school district and each year shows his students some of Gnagy’s video lessons.

TC: “How did you come to study with Gnagy in Idyllwild? “

MB: “We knew a priest at the Idyllwild Catholic church. He said, ‘I know your son is an artist. We’ve got John Gnagy.’”

Five years after that first meeting the family came to Idyllwild during Christmas break of 1971, where Gnagy gave regular “performances” at Welch’s Carriage Inn.

MB: “We just thought he’d be there; the management called him to come down. He left his warm house and trudged through the snow. He asked, ‘What do want me to draw?’ I chose a cabin in the woods, with snow on the roof.”

TC: “Can you tell us anything about Gnagy’s technical teaching?”

MB: “He did a lot of building pictures. Goldmine, lighthouses, my favorite is the mission. Always that element to put you in the picture. Landscapes, too, but the buildings… and how to use the right colors for different times of day. Atmospheric perspective. Everything becomes muted, the colors and shapes blur with distance. Basic composition. perspective. Big trees in the foreground so you felt like you were there, to welcome you to the picture.”

Henry Balzer is another professional who studied more regularly with Gnagy in Idyllwild.

TC: “How did your family find Gnagy?”

HB: “I showed a lot of promise early on. My parents were interested that I get ‘professional help’; they found he was giving lessons. Our friend [also in the book, living in Arizona now] lived in Banning at the time and knew of him. He Introduced me (really my parents) to Gnagy. We’d take the motor home; we would come out from the Redlands area, take 243. I remember being frightened, I don’t think they had as many guardrails in those days. Dad or mom would ‘camp out’ for the day. They’d find some place out of the way and park. My lessons took most of Sunday morning. I didn’t realize that he was a famous artist. Ironic[ally], I never saw his show on TV. He was a nice guy and obviously a good painter. He had developed his techniques with pastels, flexible techniques for blending.”

TC: “Can you give an example of Gnagy’s technical teaching?”

HB: “One of the things I remember learning from him is the idea of reflected light. The way that he introduced that to me we would add direct light on one side. A tree is brown; we would put a highlight on one side that was white-ish or yellowish white. But on the other side there would be this light reflected from the atmosphere that would be blue. I was hesitant; he said you have to think about all the light, all sources of illumination, each would have its own color. It looked pretty good when we added the main illumination, but then he had me get out the blue.” Henry doubted, but, “Of course he was right.”

Both artists share with the author the hope that Idyllwild will have an annual Jon Gnagy Day where youngsters can learn one of Gnagy’s lessons in an outdoor class-like setting and introduce them to the wonderful world of art and Gnagy. They both hope the Idyllwild Area Historical Society can find a spot for the artist and “famous Idyllwilder” in the museum.