By Holly Parson

Correspondent

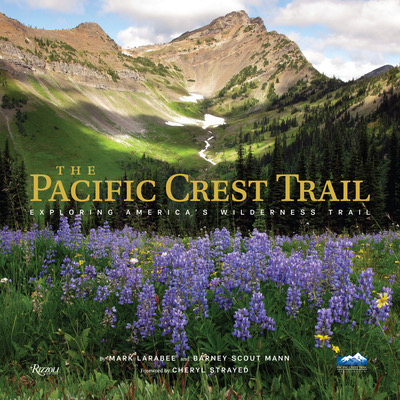

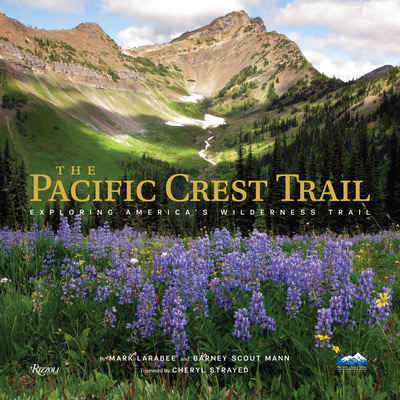

With the world-renowned Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) in the back country, this stunning collection of gorgeous vistas and character driven stories of lore is an ideal coffee table book for San Jacinto Mountain dwellers. The Pacific Crest Trail Association and Rizzoli New York published “The Pacific Crest Trail — Exploring America’s Wilderness Trail” by Mark Larabee and Barney Scout Mann.

Cheryl Strayed, author of “Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail,” wrote the forward. Its 335 pages include hundreds of panoramic images.

The trail’s origin stories impeccably capture the tone and grace of bygone eras. Section maps bring the trek’s sheer scale and endurance into focus, and it’s also a resource for wilderness hikes throughout the Rocky Mountains. Overall, the work emerges as a visual masterpiece filled with astonishing stories of collective perseverance.

Created to protect a significant sliver of the natural world, the PCT gifts ongoing generations an unprecedented legacy. More than that, this chronicle is a testimony to the spirit of freedom that permeates a 2,650-mile trail of uninterrupted natural dignity.

The book’s dedication reads: “To the visionaries — tireless volunteers, agency partners, advocates, and doners — who turned the Pacific Crest Trail dream into reality and to all those today who champion and protect it. And what a dream it was.

Why and how the PCT came into being is a story of shared vision over the course of four generations, connected by only a passion to create an adventure into the wild to be shared by nature-loving souls of daring spirit with an unquenchable thirst for freedom. Today, this collective legacy lives in the hearts of hikers and mountaineers grateful for a chance to radically meet themselves in nature’s exquisite cathedral.

“Ten thousand years ago, four great northern ice sheets retreated, laying bare a magnificent crest on the continent’s west rim.” In 1805, Meriweather Lewis and William Clark wrote extensively of the unsurpassed grandeur of the Western Sierras.

Around 1884, the first reconning of adjoining trails bubbled into the mind of 13-year-old Theodore Solomon living in Fresno. “The idea of a crest-parallel trail through the High Sierras came to me one day while herding my uncle’s cattle … I made up my mind that somehow soon I would make that journey.”

Overtaken by wanderlust and fueled by his “youthful vow,” after completing college, young Solomon brushed off his family’s career expectations and walked into the Sierra Nevada wilderness from 1892 to 1895. Resultant of his journey cutting trails, photographing, and mapping, Solomon subsequently published a trek that would come to be known in 1920 as the John Muir Trail.

It is said that “a trail can only fail once and then it is gone.”

Known as the father of the PCT, Clinton C. Clarke, born in 1873, is credited with visioning a border-to-border trail. Dan White in his book “The Cactus Eaters” described Clarke as “one part John Muir, five parts General Patton.” For decades, Clarke tirelessly championed his outsized cause. His efforts proved an unstoppable obstacle to the continuous forces of bureaucratic entropy. Writing deftly to heads of the Forest Service, National Park Service and Sierra Club, he spoke nationally on the topic from border to border. Foremostly, it was Clarke’s countless hours piecing together disparate maps that ultimately achieved the sum of its parts.

His unrepentant efforts were followed by generations of inspired outdoors men and women, aided by the Sierra Club and other outdoor clubs, who would pick up the gauntlet he set, to collectively forge this idea. Building, formally mapping and publishing the route, they locally and nationally secured legislation to fund its creation protecting contiguous routes traversing 2,650 miles of some of this nation’s most spectacular and breathtaking scenery.

No one in the early 1800s knew what the future would bring forth. Within 220 years of Lewis and Clarke’s expedition into the Sierras, the western world’s unrepentant appetite for mechanization would prove unequivocally capable of exploiting and subsequently destroying much of the natural world and many lives along with it. No one then could possibly know-how important the PCT and sister trails like the Appalachian and Continental Divide would become to generations tasked with repairing the damage.

The trail is a powerful place to meet one’s ideological peers. Professionals from a wide breadth of fields, students of all disciplines, all ages, from all walks of life, from all over the world, come together to magnify a bright light into nature’s fragile future. Each overland traveler will journey home one day, back to their communities, restored by an adventure that will never lose its mark on their being. Renewed by nature is their own very nature. Hence, they become known to themselves as stewards of the natural world.

Idyllwild is PCT hikers first resupply hub. The village is a resting place endowed with all manner of trail angels. Hikers emerge onto Highway 74 a mile east of the iconic Paradise Valley Café (PVC) having completed 151 trail miles. Usually they are hungry, dusty, tired, hot and thirsty. Servings at the PVC are generous, the Jose Burger is an iconic favorite. Just to have eaten at this café confers these nascent trekkers a badge of honor. Across the highway, if there’s space, Richard’s trail angel hostel offers immediate respite.

But it is in Idyllwild where most meet trail mates and form Tramilyh [hiking family], find a warm bed, a post office holding supplies, a Nomad Ventures to replace tech, grocery stores, a hot shower or a $5 a night campground, and let us not forget the comfort known internationally as pizza.

Getting into Idyllwild is no easy feat. In the absence of trail angels, hikers hitchhike 28 miles into town from the café, on a highway punctuated by narrow or nonexistent shoulders. This year, Idyllwild hosted hundreds of hikers. The number of permits issued on the PCT 2023 totaled 8,000. Fifty hikers per day would set out from the southern terminus over the course of three months March to May.

Refreshed, most thru hikers return to Highway 74 at PCT mile marker 151 to surmount the 58 miles of often treacherous mountain terrain, to emerge from the San Jacintos at the Whitewater Trail on Interstate 10 at Cabazon.

“Trail Angels and trail repair volunteers hold the entire PCT adventure together for hikers,” said Roland Gaebert, former California State Park manager, Idyllwild Rotary president, member of San Diego Mountain Rescue Unit and a lifelong international hiker. “Idyllwildeans, when and where else can we impact the life of a fragile naturalist at the exact moment, when they need it most?” muses Gaebert. “I see our help as a chance to deposit a memory of pure generosity hikers undoubtably pay forward. It’s another reason I love Idyllwild.”

This article was written without the use of AI.