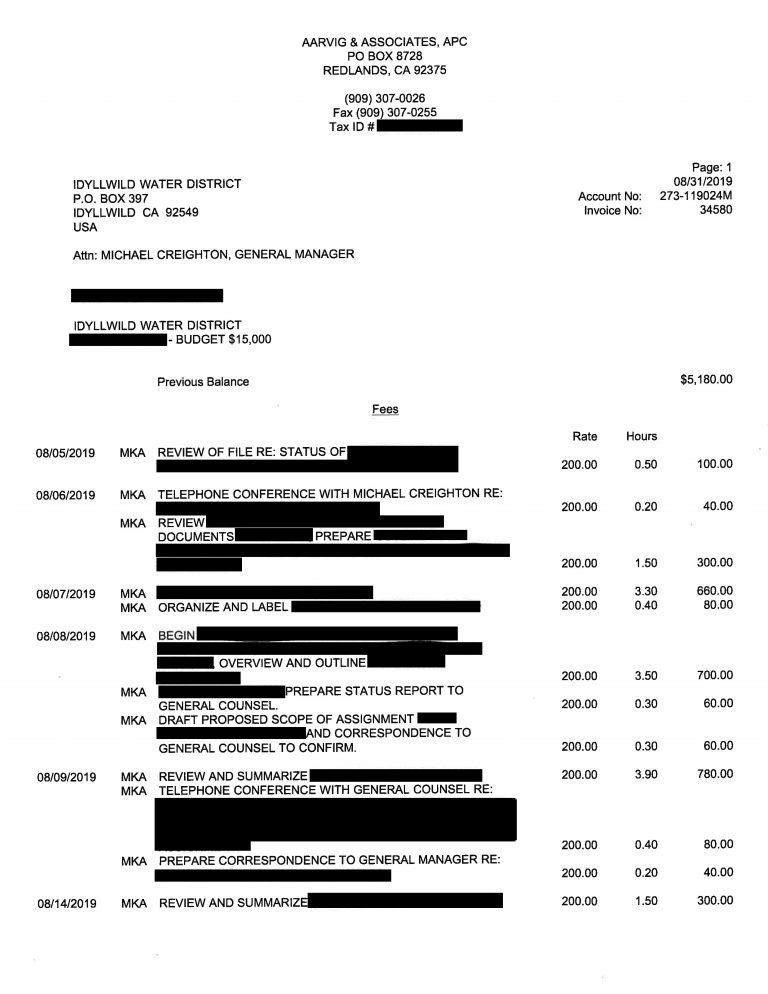

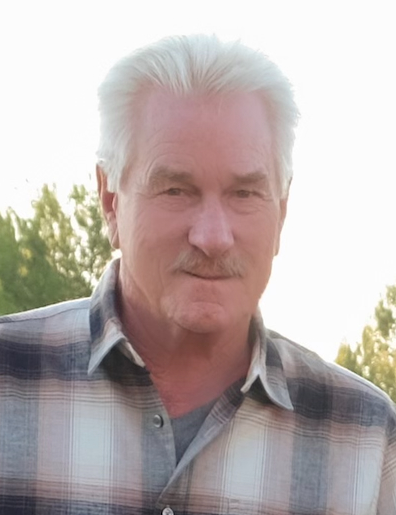

Last week the Crier sat down with Idyllwild Water District’s new interim general manager (GM) in his office to learn more about him and the values he brings to the job. Curt Sauer worked for the National Park Service for 35 years, the last eight as superintendent of Joshua Tree National Park.

PHOTO BY BRE MURILLO

His first attempt at retirement in 2010 was short lived, as he was called back to national service as an incident commander on the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. After over two-and-a-half years based in New Orleans, he was again ready for retirement, but instead applied and was hired as GM of the Joshua Basin Water District. His retirement from that position also was short.

CS: I’ve worked with the National Park Service since 1972. The first seven years was as a seasonal ranger. At that time, I worked at Rocky Mountain National Park and Grand Canyon National Park. I became permanent in 1979, as a park dispatcher for Grand Canyon National Park. My primary job there was as River Unit manager, overseeing the activities on the Colorado River. Commercial river. Concessions. It was a very political job. I had the opportunity to meet Congressman [John] McCain, before he was a senator.

After Grand Canyon I went to a place called Stehekin, which is on the east side of the Cascades. It’s a little town at the head of a 50-mile-long lake. The only access is by boat or float plane, there are no roads connecting it. There were 75 year-round residents, and 10 were National Park Service employees. I was there for three-and-a-half years as unit manager.

Then I transferred to Olympic National Park. I was there for 12 years, as East District and chief ranger. In that position I was responsible for all the administration of the ranger operations, which included law enforcement, emergency medical services, wildland firefighting, and working with the natural and cultural resource managers. After that I was fortunate enough to be selected as superintendent of Joshua Tree National Park, 2002. I retired in 2010. I was responsible for all of the park operations: maintenance, administration, budget, human resources.

Two weeks after I retired, I was contacted by the National Park Service Southeast Region office, and asked if I would be available to come back to work for two months on the BP oil spill. A “Spill of National Significance,” the first one in our country. [The largest accidental spill in history, more than 19 times as much oil as Exxon Valdez.] That two-month assignment ended up being two-and-a-half years. I was stationed in New Orleans. The Coast Guard was in charge, but there was a unified incident command. [This is the protocol for “Spills Of National Significance,” or “SONS.” Sauer was the incident commander for the Department of Interior in the multiagency unified incident command organization.]

CS: Are you familiar with the IC [incident command] system?

TC We all know fire agencies use them, but they are used for other types of events?

CS: Almost all response agencies use the Incident Command system now: search and rescue, law enforcement, EMS. [For SONS], there is the incident commander [IC] and the unified incident command. There was an IC for the states of Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi and Florida. There was a British Petroleum IC and a Department of Interior IC. The IC for the Coast Guard was responsible because of the legality. By the time I got there, there was one national park that was heavily oiled, and four national fish and wildlife reserves.

TC: So you are used to big messes?

CS: It was a huge mess and it was highly political in the states because it affected tourism, which affected all the local communities; the number of visitors that came to tourist areas was significantly reduced. Many people lost their businesses because of the oil spill. Plus, you had all the impacts to the environment. That was an interesting two-and-a-half years. We dealt with large budgets that had to be approved by the Coast Guard and funded by British Petroleum. That was the administrative part. Out in the field I had over 50 people just working on the oil spill, through the chain of command. I answered directly to the Fish and Wildlife Service supervisors and the Park Service superintendent, took their needs, brought them back to the Coast Guard, got that implemented into the plan.

TC: After the Deepwater Horizon?

CS: Then I went and took a two-month road trip, figuring out what I was going to do living in Joshua Tree. I came back, received a phone call from a local in Joshua Tree who said, “The general manager position at the Joshua Basin Water District is open and we think you should apply for it.” I applied for it, and got it, primarily I believe, because the area’s people, familiar with my actions and activities managing Joshua Tree National Park, felt that I could manage the water district.

TC: Trust?

CS: Yes. I was there for five-and-a-half years. We had 9,750 customers, 260 miles of pipeline, a hospital and a wastewater treatment plant [WWTP] that we oversaw, but I want to stress that we handled that treatment plant through an engineering firm. They handled it through another company that managed and operated it. Joshua Tree depends on tourism. Not so much Yucca Valley or Twenty Nine Palms, but everybody loves to go the Joshua Tree National Park, and so they come through Joshua Tree. I retired in 2019.

Sauer notes that he was not required to get certified (the “D” and “T” numbers that water operators have) and that GMs are not usually required to have certification. “However, I was well known in my district as a GM that was in the field. When there were emergencies I was notified, and it wasn’t uncommon for me to be out beside my workers, learning what they were doing, learning what they needed, what new or improved equipment. What I’m most proud of at Joshua Basin Water District is that we built a team out of practically the same people that were there when I arrived, and removed the lack of communication between administration and operation, with the full support of the board.’

Sauer also said that as an interim GM he hoped to “have a program in place that the new general manager can implement.”

TC: So you see your job as making life easier for the next guy?

CS: Or next gal.

TC: The GM is in charge of hiring and firing?

CS: It’s much more than hiring and firing. It’s building a team. The GM serves at the pleasure of the board. The GM is responsible for developing a cohesive program which the board approves for implementation through the budget and capital improvement plan. It includes human resources management, it includes training, safety, long-term and short-term planning. Fortunately, there was a rate study that was recently completed, so we won’t need another rate study, but the next GM will.

TC: Can you tell us anything you’ve learned in your first few days here?

CS: This is day four. I’ve learned that we have a very supportive board of directors, we have a WWTP [waste water treatment plant] and distribution system that meet state standards. I haven’t had the opportunity to learn much about Idyllwild itself because of the weather, but I’ve already met some really nice people.

TC: Is building a new sewer plant is a big undertaking for a small district?

CS: It was a large project in the ’60s or ’70s. [The plant came online in 1970.] Its 50 years old. My understanding is that initially Pine Cove, Idyllwild and Fern Valley were talking about doing it together; it turned out Idyllwild did it itself. They issued a bond. That bond is paid off, a 30-year bond. I haven’t had time to get into the specifics of why [it] needs to be redone. But 50 years is a long time for a treatment plant, and it is still functioning.

I asked about the WWTP only serving 600 customers but having more capacity and Sauer pointedly asked “commercial or residential customers?”; those downtown businesses serve a lot of people.

CS: 50 years ago where were we? When we build another WWTP we need to think about where we will be in 30 years and 50 years, and maybe build it to that capacity. I never thought that I would see Joshua Tree go from … when I left there in 2010, we were just getting to one-and-a-half million visitors. There’s 3 million visitors now. They all go through Joshua Tree, Twenty Nine Palms, they all drink water and they all flush toilets. Our water table, fortunately, up there is a good 400 feet underground. The water table here is anywhere between 8, to, during drought, a 100 and some … its right there. You put your septic tank in, that effluent goes down and at some point in time it’s going to meet the ground water. So as the population grows, or as visitation grows, you have an increased threat to the ground water. You can wait until the ground water is polluted or you make plans in advance, so you can treat it, so that it doesn’t get polluted.

TC: Rules are getting more stringent for septic tanks?

CS: In some cases, that’s what I have heard. Big picture, [yes,] which is a problem for small communities.

TC: I don’t want to tear my tank out and pay $50 a month for sewage, but I understand why that may be a good idea.

CS: To add additional sewage connections you need to run new sewer lines … it’s not on our immediate horizon.

Sauer is presently living in the Cherry Valley area, but is undeterred by our local snowfall; he was there Thursday morning as the town dug itself out of the first deep snow of the year.

TC: You’re not afraid of snow?

CS: When I lived in Rocky Mountain National Park, when I lived in Stehekin in the North Cascades, there’s a lot of snow. I have the experience of driving in snow. Mostly I have the experience of knowing how other people drive in snow.

Sauer added that he was looking forward to meeting Idyllwild Fire Chief Mark LaMont as well as Pine Cove and Fern Valley water districts’ GMs, activities for his second week on the job.