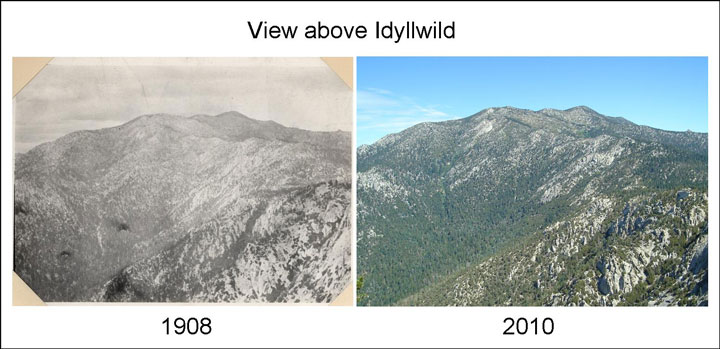

Photo (left) by Joseph Grinnell (1908) and photo (right) by Dr. Lori Hargrove (2010)

“The goal is not to try to live forever. The goal is to create something that will.” -- Fred Rogers

More than 100 years ago, scientists had already begun to flock to the San Jacinto Mountains to study the unique and diverse wildlife that inhabits our chaparral, mixed forest, riparian and meadow habitats. Our sky island separates local wildlife from the surrounding ecological communities and allows them to evolve in isolation from their ancestors. The effect is similar to geographic isolation in rural Appalachia. That is, geographically isolated populations are also genetically isolated. Consequently, for many species, the San Jacintos have given rise to a branch of the family tree that is distinctly different from the rest of their kind down the Hill and across the pass to the San Bernardino Mountains. Geographic isolation also means there are fewer immigrants that populate our region from outlying areas. When populations dwindle, few outsiders repopulate the hill.

In 1908, Idyllwild was just developing as a tourist destination. That year, two scientists from UC Berkeley, Joseph Grinnell and Harry Swarth, conducted an expedition to survey the fauna of the San Jacintos, including areas nearby Idyllwild County Park, Humber Park, Fuller’s Mill and the James Reserve. Their survey data along, with detailed notes, photographs and the collection of archived specimen, created a baseline for future generations to use as a benchmark for environmental change. In 2011, a team of biologists from the San Diego Natural History Museum began to resurvey the 20 sites established by Grinnell and Swarth. The centennial resurvey concluded in 2014. In 2016, the San Diego Natural History Museum will publish survey results that span across the last century. Here’s a sneak preview of the results:

1908 vs. 2015

Species nearly vanished or locally extinct since 1908.

• Mammals — San Bernardino flying squirrel, voucher specimen collected in Strawberry Valley in Idyllwild (1908). The JR is collaborating with the SDNHM to intensively survey for flying squirrels around Idyllwild.

• Herpetofauna — Rubber boa, last collected in 1982.

• Amphibians — Mountain yellow-legged frog (federally endangered), a species common in Idyllwild area only a few decades ago.

• Birds — the Black-chinned Hummingbird, Gray Vireo, Warbling Vireo, Chipping Sparrow, Lark Sparrow and Yellow Warbler.

Species that are new arrivals since 1908.

• Mammals — Desert cottontail and brush rabbit.

• Birds — the Red-shouldered Hawk, American Crow, American Robin, European Starling, House Sparrow and Brown-headed Cowbird .

Species that have been detected with new technology.

• Mammals –—Twelve species of bats!

Why have some species disappeared from Idyllwild while others have colonized it? There is no single answer. Some species have spread to higher elevations, retreated from lower elevations, spread to lower elevations, retreated from higher elevations, attraction to urban development or retreated from urban development. The Mountain Quail, Song Sparrow, California Towhee, and Tiger or Western Whiptail appear to have spread to higher elevations. At the same time, some species breed at lower elevations than a century ago, such as the Red-breasted Sapsucker.

What are the consequences of our changing landscape? Predicting and mediating the biological impacts of habitat disturbance remains a great challenge for science and an area of research the James Reserve is actively engaged in. In fact, Janet Napolitano, president of the University of California system, has just awarded a large grant to a team of UC researchers led by Drs. Barry Sinervo and Laurel Fox (UCSC), to monitor climate change across the state of California, including at the James Reserve. Stay tuned for more about that project, and to learn more about the UC president’s award, visit www.ucnrs.org/

nrs-climate-research-gets-uc-presidents-2m- research- award.html.