Last week the Crier took a tour of Idyllwild Water District’s (IWD) wastewater treatment plant, in service since 1970. IWD recently approved a five-year program of rate increases to pay for a replacement for the facility, at a projected cost of over $7 million. Funding also is being sought from the state to lift some of that burden from rate payers. Unless a majority of the district’s sewer customers submit written protests before the end of the June 21 public hearing, the 13% a year rate hikes will begin to show up on bills and the project will go forward.

PHOTO BY DAVID JEROME

Before the tour, IWD General Manager Leo Havener and Chief Financial Officer Hosny Shouman answered a few questions about the rate study and the proposed new plant.

Q: The new plant will have increased staffing?

LH: The proposal adds one new employee this year, so there will be two.

Q: The rate study assumes little growth in water consumption, and income from water?

LH: Correct.

Photo by David Jerome

Q: What is the distribution of sewer services between commercial and residential customers?

HS: Residential accounts: 422; commercial accounts:165. Residential EDUs [equivalent dwelling unit]: 460; commercial EDUs: 952.

Q: The study assumes annual inflation of 5%, but it has been historically below 3%.

HS: I looked up the rate last night, it was 9.1%.

We learned at recent public meetings that the plant’s capacity is 250,000 gallons per day, but normal flow is around 110,000. During wet winters, influx and infiltration raise the flow over 200,000. The system has room for expansion. It serves District 1 of IWD’s map. If a developer wants a new branch within that zone, they would have to request it and “work with the district.” Expanding service beyond District 1 would require Local Agency Formation Commission approval. The new plant will have the same capacity. Raising it would require new permitting.

Photo by David Jerome

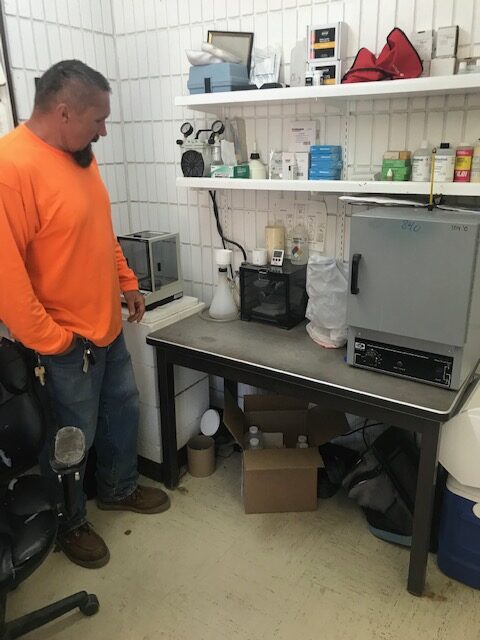

Operator III Danny Campbell, charge of its day-to-day operation, led the tour of this piece of Idyllwild’s aging critical infrastructure.

The raw sewage enters the plant at the “headworks,” a concrete sluice. Here it is filtered through a perforated metal screw-shaped screen in an auger. When the level in the sluice rises, indicating a clogged filter, the auger takes a turn and exposes clear filter. This removes coarse debris. Things like concrete and asphalt turn up. And rags, lots of rags.

The raw “input” is sampled in a refrigerated closet adjacent to the headworks. The refrigeration ensures that the sample reflects the condition of the waste entering the system, before the plant’s micro-organisms have gone to work. Samples are regularly tested in the district’s own on-site lab and records kept. Samples from various points in the process also go to the Santa Ana Regional Water Quality Control Board.

“Sometimes we get violations. This place is old,” said Campbell. The regulating agencies can “force rapid repairs,” and getting things fixed quickly is always more expensive, he said.

The wastewater is split. Depending on flow, some may go into a holding, or “equalization” basin. The rest goes on to secondary treatment. At night, when flow goes down, the equalization basin keeps the secondary treatment running.

The main component of the system is secondary treatment, a circular tank with three sections; 33,000 gallon anoxic (no dissolved oxygen), 88,000 gallon aerobic, and 40,000 gallon settling or clarifying areas. Here, biodegradable organic material is digested by microbes. The water in the first section is opaque and muddy looking, by the third if begins to resemble pond water.

Water is recirculated between the three sections by pumps, so the water will have passed through the sections several times before leaving secondary treatment. The tank has a skimmer on the surface and a scraper on the bottom to remove scum and sludge. A pair of powerful air pumps, located next to the office and lab, pump air through a huge hose to aerate the aerobic tank. Here a visitor notes one of the most visible work arounds in the present plant: the old underground pipe is hopelessly corroded, and now an immense black hose snakes across the office stairs (watch your step) and the asphalt yard, to the tank.

Around the plant are various control panels no longer being used because they are no longer compatible with newer equipment. Sophisticated-looking 1960s-era control panels sit unused, replaced by what looks like home sprinkler timers. A desktop computer in the lab runs an old Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition system. It still monitors input and output, and does connect to cell phones to inform staff of anomalies, but is “no longer real time,” as there is a five-minute delay, making it useless for fine adjustments.

A generator exists for backup with an automatic system to bring it online in the event of a power outage. The system is biological and has to be kept alive.

In the main pump room sit two large pumps that move the mass of water through the plant. One is idle — a dropped tool disabled it and repairing it will require demolition. The problem lies beneath 6 feet of concrete. Temporary plumbing keeps the system going. The pump room also contains chlorine. Campbell said, “We don’t typically add a lot of chemicals.” The process is mostly the work of microbes and the chlorine just slows them down when needed.

Other machinery includes a skip loader, a forklift, and Campbell’s favorite, the Hot Jet. This machine has its own boiler for hot water to clean out clogged pipes. It can provide boiling water but is usually set for 150°, safer for plastic pipes. “FOG,” Fat, Oil and Grease, can choke an 8-inch pipe down to 5 inches, causing sewage to back up and overflow from maintenance holes.

After the secondary treatment, the water goes to seven ponds. A filled pond, #6, was ringed by reeds and covered with algae, and a pair of ducks with three ducklings were visiting. The ponds are used in rotation with passive “fail-safes” to prevent them from overflowing. If the inlets are clogged the water will still have a pond to contain it. This gives Campbell “about 700,000 gallons of time to figure out what’s up,” about a week.

Near one dried-out pond, Campbell pointed out th4e “rag shed” where the material the auger separated out is left to dry out. Quite a pile. Sometimes Campbell shovels the dried sludge around by hand, moving it in wheelbarrows. The sludge dries out, and at the end of the dry season is hauled away by 10-cubic-yard dump trucks. It may end up in landfills, fertilizing nonedible agriculture, or incinerated to generate electricity.

Downhill from the ponds are monitoring wells. These are tested quarterly and the results submitted to the state. Water from the ponds is percolating into an aquifer, albeit one downstream from Idyllwild. Laws require the testing, and specify the distance between these ponds and any inlet of a drinking water system.

The ponds will still serve the projected new plant, and the old plant will be patched up and kept as reserve.

A dive into back issues of the Crier allows a recreation of the chronology of the original plant’s construction. Groundbreaking occurred in January 1969. At that time, the project was projected to cost $1 million. In February 1970, the Crier announced that the last foot of sewer pipe had been laid, and that the system would be in operation by spring. In March, we read that testing had discovered a few pieces of broken pipe. April brought the news that those “few” leaks amounted to 101 failures in 291 sections of pipe, the failures attributed to “rocky terrain.” In May the contractor was working on “extended time” to get the system ready for service.

The June 5 edition includes a photo of the first sewer connection, at the home of IWD Sanitation Engineer Wilson Smith. Plumber Emeritus Chuck Kretzinger was among the handful of attendees at that historic event. By June 26, we see the ponds filling up and read that birds are already discovering them. By March 1971, the Crier had a photo of local school kids taking a tour, walking out on the “gangway” over the main tank.

In November of that year, former Idyllwild Chamber of Commerce President Wilson G. Smith wrote a letter to the editor touting the organization’s accomplishments, topping the list with starting, in 1961, the “movement that culminated in our present sewage treatment system.” The project took, from first arguments to first flush, about 10 years and a million dollars. That $1 million in 1970 would be equal to over $7.8 million today. The original price also included the pipes and the drying ponds, which will continue to serve.