The largest wildfire in Arizona history was contained barely a month ago. The Wallow Fire burned nearly 540,000 acres from late May until its containment on July 21. During its 2-month burn, the Wallow grew to more than twice the size of the 2003 Cedar Fire (273,000 acres), the largest California wildfire, more than three times the size of the 2009 Station Fire (160,000 acres), and burned more than 13 times as much acreage as the 2005 Esperanza Fire.

From the tons of ashes produced from a gigantic conflagration, the Forest Service has already gleaned lessons, which apply throughout the West, but are particularly relevant to the Hill, according to Idyllwild Fire Chief Norm Walker.

Walker was the incident commander on the Forest Service Interagency Management Team (SoCal Team 1) that was called into service to help fight the Wallow Fire. He was on site from June 16 through June 29. The fire started on May 29 and burned mostly northeast within the Apache - Sitgreaves National Forests east of the White Mountain Indian Reservation.

The largest previous Arizona fire was the 2002 Rodeo - Chediski Fire just east of the Wallow. Two years later in 2004, the Forest Service collaborated with local partners such as the White Mountain Apache tribe and the state to initiate fuels treatments projects on thousands of acres.

While much of the Wallow burn area was flat plains of grass, many acres of forest burned, too. The treatments were visibly effective and critical to limiting damage to structures, according to Walker.

The area and small towns reminded him very much of Idyllwild and its environs. And, the five years of fuels treatments protected these residential areas.

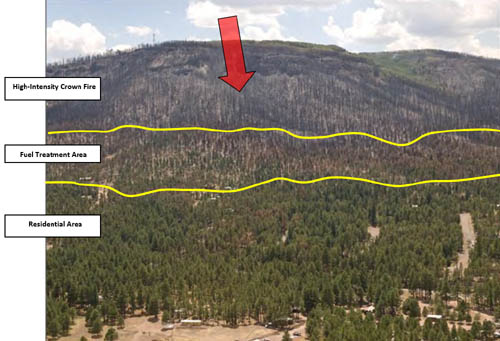

“In many places, as the flames came out of the forest into the treated areas, they dropped to the ground [from the crowns] and in some cases, went out by itself,” Walker said during his presentation last week.

The recently released Forest Service report, “How Fuel Treatments Saved Homes from the 2011 Wallow Fire,” summarized the prevention activities near Alpine, Ariz., this way, “As the main fire enters the … White Mountain Stewardship Fuel Treatment units located above Alpine, the blaze drops from up in the tree crowns down to the surface level. The fire’s rate-of-spread dramatically slows. Thanks to the influence of these previously developed treatment units—implemented beginning in 2004 — flame lengths are now low enough to allow firefighters to safely attack the fire and protect homes and property.”

In the same report, the Fire Office for the Alpine Fire District said, “Without the fuel treatment effects of reducing flame lengths and defensible space around most houses, we would have had to pull back our firefighters. Many of the houses would have caught fire and burned to the ground.”

The report included many photos, which dramatically contrasted the devastating results of the fire in the forest and the transition from black to brown to green where the fuels treatments occurred.

Both Walker and the report authors emphasized how the treatments blunted the full power of the fire and allowed firefighters to stay near homes and protect them from the vast fire.

“It was good to see a similar program tested in a big way,” Walker concluded. “The abatement we do here has a bigger effect on whether your house is saved than what [firefighters] can do [onsite]. Chances are an engine won’t get to your home.”

A longtime advocate of thinning and other treatments, Walker is an even stronger proponent of localities implementing treatment programs to enhance their safety.